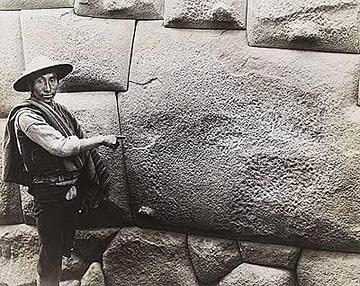

Hatunrumiyoc – Great Stone

This building, found on the street typically taken by tourists up to the modern district of San Blas and its bars, is from this time in Inca history. What it’s real name is no-one knows. The street is called Hatun Rumiyoc, a name given to it in much more recent times that in Quechua means big stone, supposedly referring to the famous 12-angle stone found in the wall half way up the street. This Inca building, which contains this stone, is in turn named after the street that is named after the stone. If the people of Cusco at the time of the conquest knew what the building’s name was, or who for sure built it, they unfortunately didn’t tell or were not asked by any Spanish chronicler.

Colonial rebuilding attempts

So it is said, based on common opinion, that the building was the palace of Inca Roca, the sixth Sapa Inca who ruled sometime around 1350. But the Qoraqora, another building that is located on the plaza, is also said to be his palace. Perhaps they both were, or perhaps the Hatunrumiyoc was Sinchi Roca’s palace 100 to 150 years before. There’s no way to be sure who built it and when, and like the Incas, we have taken to inventing history for our own purposes. Maybe, contradicting the modern “inventions” of those academics who try to make sense these things today, one of the more fabulous local tales is true. One states that Inca Roca only rebuilt the structure, which had been in ruins for a unknown period of time, from the existing bricks he found scattered around. Who knows?

By Martin Chambi

What we do know about Hatunrumiyoc is that it is exquisitely constructed, reaching the same perfection of many other Inca structures. There were two main building styles used in Inca architecture, aligned rectangular bricks and complex jigsaw-like polygonal bricks like those used here and in Sacsayhuamán. Although the walls of polygonal bricks look more complex, perhaps they were easier to carve and set, mostly left in the natural shape in which they were found? (The Incas didn’t quarry stone, they collected from landslides) Regardless, it is this building style the allowed Inca architects get away with some really cool tricks.

Water engineer Ken Wright estimates that 60 percent of the Inca construction effort was underground. The Inca built their cities with locally available materials, usually including limestoneor granite. To cut these hard rocks the Inca used stone, bronze or copper tools, usually splitting the stones along the natural fracture lines. Without the wheel the stones were rolled up wood beams on earth ramps. Extraordinary manpower would have been necessary. Hyslop comments that the “ ‘secret’ to the production of fine Inca masonry…was the social organization necessary to maintain the great numbers of people creating such energy-consuming monuments.”

Usually the walls of Incan buildings were slightly inclined inside and the corners were rounded. This, in combination with masonry thoroughness, led Incan buildings to have a peerless seismic resistance thanks to high static and dynamic steadiness, absence of resonant frequencies andstress concentration points. During an earthquake with a small or moderate magnitude, masonry was stable, and during a strong earthquake stone blocks were “ dancing ” near their normal positions and lay down exactly in right order after an earthquake.

Another building method was called “pillow-faced” architecture. Pillow faced building was achieved by using fired adobe bricks and mud mortar. The Incas would then sand large, finely shaped stones coated in mud and clay. Then they would fit the bricks and stones together using the mud mortar into jigsaw like patterns. Pillow-faced architecture was typically used for temples and royal places like Machu Picchu.

- (Spanish) Vergara, Teresa. “Arte y Cultura del Tahuantinsuyo”. Historia del Peru. Editorial Lexus, 2000. ISBN 9972-625-35-4

- (Spanish) Agurto, Santiago. Estudios acerca de la construcción, arquitectura y planeamiento incas. Lima: Cámara Peruana de la Construcción, 1987.

- Gasparini, Graziano

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario