tourism in Peru

lunes, 16 de marzo de 2015

martes, 25 de marzo de 2014

PARACAS ELONGATED SKULLS

DNA Analysis Of Paracas Elongated Skulls Released. The Results Prove They Were Not Human

Paracas is a desert peninsula located within the Pisco Province in the Ica Region, on the south coast of Peru. It is here were Peruvian archaeologist, Julio Tello, made an amazing discovery in 1928, a massive and elaborate graveyard containing tombs filled with the remains of individuals with the largest elongated skulls found anywhere in the world.

http://www.sunnyskyz.com/good-news/545/DNA-Analysis-Of-Paracas-Elongated-Skulls-Released-The-Results-Prove-They-Were-Not-Human

domingo, 30 de septiembre de 2012

2,800 YEAR OLD TOMBS

domingo, 12 de febrero de 2012

- THE SACRED LORD OF SIPAN

The Lord of Sipán (El Señor de Sipán) is the name of a mummy of an elite man found in Sipán by Peruvian archaeologistWalter Alva in 1987. The tomb is in Sipán's Huaca Rajada, an area in Chiclayo.

The Lord of Sipán tomb is a Moche culture site in Peru. Some archaeologists hold it to be one of the most important archaeological discoveries in this region of the world in the last 30 years, as the main tomb was found intact and untouched by thieves.

Sipán is located in the northern part of Peru, close to the coast, in the middle of the Lambayeque Valley, 35 km east of Chiclayo, Peru. Four tombs have been found in Sipán's Huaca Rajada. This was a burial mound, a kind of mausoleum, built by the Moche culture. Its people ruled the northern coast of Peru from around 1 AD to 700 AD.

The town of Sipán, in the Zaña district, is roughly around 20 miles east of the city of Chiclayo and 45–50 miles away from Lambayeque. The site belonged to the Moche (Mochican) culture that mainly worshipped the god called Ai Apaec (Ayapec) as "principal" god or deity.

The clothing of this warrior and ruler suggest he was approximately 1.67 m tall. He probably died within three months of governing. His jewelry and ornaments indicate he was of the highest rank, and include pectoral, necklaces, nose rings, ear rings, helmets, falconry and bracelets. Most were made of gold, silver, copper and semi-precious stones. In his tomb were found more than 400 jewels.

The Lord of Sipán was wearing a precious necklace with beads of gold and silver in the shape of maní (peanuts) represent the tierra (earth). The peanuts symbolized that men came from the land, and that when they die, they return back to the earth; the Moches harvested peanuts for food. The necklace has 10 kernels to the right, which are gold, signifying masculinity and the sun god, while the kernels on the left side are silver, to represent femininity and the moon god.

Below the tomb of the Lord of Sipan, two other tombs were found: that of a priest and of the Old Lord of Sipan. DNA analysis of the remains established that the priest was contemporary with the Lord of Sipan. Artifacts in his tomb are believed to be related to religion: the cup or bowl for the sacrifices, a metal crown adorned with an owl with its wings extended, and other items for worship of the moon.

DNA analysis of remains of the Old Lord of Sipan proved that he was a direct ancestor of the Lord of Sipan. In his tomb were found the remains of a young woman, a likely sacrifice to accompany him to the next life. Also there were sumptuous costumes embroidered with gold and silver.

The Royal Tombs Museum of Sipán houses most of the important artifacts which Dr. Walter Alva Alva found in 1987. He helped found and support construction of the museum, which opened in 2002. The museum is located in the town of Lambayeque, Peru. (which also happens to be in the "state" of Lambayeque) in Peru. The museum was designed to resemble the ancient Moche tombs (with the exception of giant golden figures on the side).

The museum's main attraction is the Lord of Sipan and his entourage, who accompanied him to the afterworld with him. The warriors who were buried with him had amputated feet, as if to prevent their leaving the tomb. The women were dressed in ceremonial clothes. Dogs, llamas, and more than 80 huacos (works of ceramic pottery) were also buried in the tomb.

Wikicredits.

lunes, 23 de enero de 2012

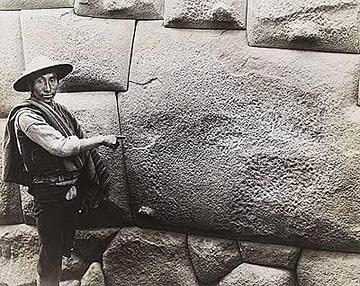

- 12 ANGLE STONE

Hatunrumiyoc – Great Stone

This building, found on the street typically taken by tourists up to the modern district of San Blas and its bars, is from this time in Inca history. What it’s real name is no-one knows. The street is called Hatun Rumiyoc, a name given to it in much more recent times that in Quechua means big stone, supposedly referring to the famous 12-angle stone found in the wall half way up the street. This Inca building, which contains this stone, is in turn named after the street that is named after the stone. If the people of Cusco at the time of the conquest knew what the building’s name was, or who for sure built it, they unfortunately didn’t tell or were not asked by any Spanish chronicler.

Colonial rebuilding attempts

So it is said, based on common opinion, that the building was the palace of Inca Roca, the sixth Sapa Inca who ruled sometime around 1350. But the Qoraqora, another building that is located on the plaza, is also said to be his palace. Perhaps they both were, or perhaps the Hatunrumiyoc was Sinchi Roca’s palace 100 to 150 years before. There’s no way to be sure who built it and when, and like the Incas, we have taken to inventing history for our own purposes. Maybe, contradicting the modern “inventions” of those academics who try to make sense these things today, one of the more fabulous local tales is true. One states that Inca Roca only rebuilt the structure, which had been in ruins for a unknown period of time, from the existing bricks he found scattered around. Who knows?

By Martin Chambi

What we do know about Hatunrumiyoc is that it is exquisitely constructed, reaching the same perfection of many other Inca structures. There were two main building styles used in Inca architecture, aligned rectangular bricks and complex jigsaw-like polygonal bricks like those used here and in Sacsayhuamán. Although the walls of polygonal bricks look more complex, perhaps they were easier to carve and set, mostly left in the natural shape in which they were found? (The Incas didn’t quarry stone, they collected from landslides) Regardless, it is this building style the allowed Inca architects get away with some really cool tricks.

Water engineer Ken Wright estimates that 60 percent of the Inca construction effort was underground. The Inca built their cities with locally available materials, usually including limestoneor granite. To cut these hard rocks the Inca used stone, bronze or copper tools, usually splitting the stones along the natural fracture lines. Without the wheel the stones were rolled up wood beams on earth ramps. Extraordinary manpower would have been necessary. Hyslop comments that the “ ‘secret’ to the production of fine Inca masonry…was the social organization necessary to maintain the great numbers of people creating such energy-consuming monuments.”

Usually the walls of Incan buildings were slightly inclined inside and the corners were rounded. This, in combination with masonry thoroughness, led Incan buildings to have a peerless seismic resistance thanks to high static and dynamic steadiness, absence of resonant frequencies andstress concentration points. During an earthquake with a small or moderate magnitude, masonry was stable, and during a strong earthquake stone blocks were “ dancing ” near their normal positions and lay down exactly in right order after an earthquake.

Another building method was called “pillow-faced” architecture. Pillow faced building was achieved by using fired adobe bricks and mud mortar. The Incas would then sand large, finely shaped stones coated in mud and clay. Then they would fit the bricks and stones together using the mud mortar into jigsaw like patterns. Pillow-faced architecture was typically used for temples and royal places like Machu Picchu.

- (Spanish) Vergara, Teresa. “Arte y Cultura del Tahuantinsuyo”. Historia del Peru. Editorial Lexus, 2000. ISBN 9972-625-35-4

- (Spanish) Agurto, Santiago. Estudios acerca de la construcción, arquitectura y planeamiento incas. Lima: Cámara Peruana de la Construcción, 1987.

- Gasparini, Graziano

sábado, 21 de enero de 2012

- CARAL: LA CIUDAD ANTIGUA

La arqueóloga peruana Ruth Shady, quien dirigió las investigaciones en el sitio arqueológico de Caral, unos 200 kilómetros al norte de Lima, aseguró que esta ciudadela "es de lejos la más antigua de América" y rompe la concepción que se tenía hasta hoy de los más antiguos centros urbanos en el mundo. La ciudad fue descubierta en 1905 pero la ausencia de cerámica, y otros datos que faltaban, no permitieron que los arquéologos se dieran cuenta de la antigüedad de este sitio.

"No hay en América otro sitio que tenga similares características sino hasta 1000 ó 1500 años después", manifestó Shady, quien estudió desde 1996 los restos arqueológicos del valle costero de Caral, en el centro norte del Perú.

Shady señaló que hace años ya se manejaba la hipótesis de que Caral era la ciudad más antigua de América, pero no fue comprobado hasta que se tuvieron los resultados de las pruebas del radio carbono (carbono 14) en restos de fibra recuperados en varias zonas del lugar.

"Esos resultados nos permiten afirmar que esta ciudad fue construida por una sociedad con una organización sociopolítica de nivel ya estatal, que controlaba la productividad de un área mucho mayor que la del valle de Supe (al norte de Lima), y que había construido asentamientos de tipo urbano a lo largo de este valle", señaló.

Según las pruebas científicas, Caral tiene una antigüedad promedio entre 2.627 y 2.100 años antes de Cristo aproximadamente y dijo que en el resto de América "el desarrollo urbano comienza 1.550 años después que en Perú".

Shady señaló que Caral, donde fueron halladas pirámides de más de 150 metros de planta, muros de hasta 20 metros de elevación y grandes plataformas de piedra, "habría tenido entre 500 y 600 años de ocupación".

La arqueóloga añadió que "en honor a la verdad" fue un equipo de arqueólogos de la Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos (UNMSM), decana de América, el que estudió primero la zona y determinó que se trataba de la ciudad más antigua del continente.

En este sentido enfatizó que el antropólogo del Field Museum de Chicago (EEUU) Jonathan Haas y Winifer Krammer, de la Universidad de Illinois, sólo contribuyeron con un aporte económico para poder realizar doce de las pruebas de carbono, ya que el resto fueron pagadas por Betty Meggers del Smithsonian Institution.

"Haas y Krammer vinieron a Caral y han colaborado para obtener las muestras que se enviaron (a EEUU) para la datación y estamos coordinando la posibilidad de un trabajo conjunto en el futuro para profundizar los estudios sobre la sociedad y cultura de Supe", indicó.

La también directora del Museo Arqueológico de la UNMSM mantuvo que Caral rompe "todos los esquemas" que tenían los arqueólogos respecto a que las civilizaciones complejas sólo pueden florecer en un período en el que exista la cerámica.

"A diferencia de otros sitios del período arcaico lo importante de Caral es que es monumental, por eso nadie creía que era del pre-cerámico", manifestó.

Caral, explicó Shady, tiene más de 65 hectáreas de extensión y desde 1996 los arqueólogos peruanos iniciaron las excavaciones de las 32 estructuras piramidales.

"Hemos excavado hasta la fecha tres estructuras piramidales de diferente rango, extensión o tamaño y estamos excavando cuatro sectores residenciales, diferenciados por su ubicación, por su tamaño y la calidad del material constructivo", señaló.

Caral, precisó, tuvo a diferencia de las sociedades agrícolas de su época una economía mixta que se sustentaba en actividades agrícolas y pesqueras, sus habitantes consumieron grandes cantidades de anchoveta y hubo un intenso comercio del algodón.

"En Caral se han encontrado productos de la sierra y de la selva", lo que demuestra que hubo un "intercambio sostenido a pesar de las dificultades para la comunicación en un territorio como el área del norte centro atravesado por la Cordillera de Los Andes", señaló Shady.

"Era una sociedad con una organización muy compleja para su época. Ha tenido un desarrollo precoz más avanzado que su vecinas del territorio americano", afirmó. En Caral fueron hallados hace algunos años los restos de un niño de algo más de un año, del 2.300 antes de Cristo, que fue sacrificado y enterrado antes de construir un sitio residencial. También se encontraron, en una de dos tumbas saqueadas, restos de cabellera cortada, que se exhiben hoy en el Museo Arqueológico que posee la Universidad San Marcos, en el centro de Lima.

Shady explicó que aún hay que establecer cómo fue la jerarquía de estos centros urbanos, qué tipo de estructura social permitió su organización.

TURISMO

El día 2 de noviembre de cada año se realiza una visita guiada a la Ciudad Sagrada de Caral; los visitantes podrán apreciar las impresionantes edificaciones monumentales como la Pirámide Mayor, el templo del Anfiteatro, Pirámide de la Galería, Pirámide de la Cantera, Pirámide de la Huaca, Pirámide Menor y el Templo del Altar Circular además, de los distintos sectores residenciales.

Las excavaciones efectuadas permiten mostrar las expresiones culturales del proceso civilizatorio de la sociedad de Supe que data entre 5 000 y 4 000 años al presente; sociedad contemporánea con la egipcia en el período de construcción de las pirámides de Giza y con la de Mesopotamia durante el auge de las ciudades sumerias.

La sociedad de Supe avanzó en conocimientos y en organización social, adelantándose a otras sociedades del continente americano en, por lo menos, 1 500 años.

Caral se encuentra en el valle de Supe a la altura del kilómetro 182, al norte de Lima y a 23 km de la carretera Panamericana.